Tim Burton’s Willy Wonka Movie Is Still the Most Faithful Adaptation of Roald Dahl

Paul King may be returning to the Gene Wilder original with the Wonka prequel, but Tim Burton's 2005 film remains closer to Roald Dahl (with some caveats).

Wonka, the phantasmagorical musical starring Timothée Chalamet as the world’s most famous chocolatier, opens in cinemas in time for the holiday season this week. The film, directed by Paul King of Paddington fame, arrives on the big screen with a lot of audience skepticism. We already have two very popular adaptations of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl’s most beloved novel, and the idea of a prequel following young Willy Wonka feels unnecessary given that the book isn’t exactly about him. Still, there is a reason that Dahl adaptations remain popular, even as the author long faced pushback for some of his more bigoted views.

People love Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, first published in 1964, because it’s as delicious as the confectionaries made by Wonka. The story of five varied children who win a contest to tour a secretive factory is cheeky, strange, occasionally grotesque, and extremely funny. Dahl endures because he never talked down to his young audience and understood that they were far smarter and crazier than staid parents and teachers would have us believe. Sugar is great, but sometimes you need that dash of spice in the mixture. This unique blend of Dahl-isms also makes him an unexpectedly difficult author to adapt, as both cinematic adaptations of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory prove.

In 1971, we got a commercial flop that became a childhood favorite for generations to come afterward, and then 34 years later, the most famous Goth auteur in Hollywood remade it. Fans have spent close to two decades arguing over which version is better, or at the very least most faithful to Dahl’s unique vision. The race is tight and more complex than you’d imagine… yet it may be the lesser loved of the two films that got closer to Dahl’s worldview.

What Works About the 1971 Film

Directed by Mel Stuart, 1971’s Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory was part movie, part confectionary ad. Paramount made a splashy deal with Quaker Oats to use the film as a vehicle to introduce real-life Wonka Bars to America. Dahl signed on to direct a screenplay but never delivered a completed one by the time production started. It was the early ‘70s and musicals were still a big thing in Hollywood so they, of course, added some songs. The idea was to make something universally appealing to kids and adults alike, which seemed very in line with Dahl’s ethos. The problem was that a new writer was brought in to do an uncredited rewrite of Dahl’s screenplay against his wishes. Dahl publicly disowned the movie and ranted about it for decades. Still, there is much in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory that feels appropriately Dahl-esque.

In this movie, Charlie Bucket, our impoverished but plucky protagonist played by Peter Ostrum, is more well-rounded. He’s eager to win the Golden Ticket and you can sense his disappointment with the world that, by circumstance of his birth, he’s unlikely to get one. His genuine joy at entering the factory is a needed contrast with the other ticket winners, who only seem to want it because it’s something they can easily acquire (they’re also far brattier than the kids in the Burton movie, so watching them suffer is just funnier!)

What the ’71 film does best is its portrayal of Wonka. Gene Wilder is so magnetic and mischievous that it’s hard to imagine the role wasn’t written for him (Dahl wanted Spike Milligan). We don’t see Wonka until halfway through the film, and his introduction, where he seems frail and shaken before tumbling into a somersault, immediately makes him seem both wondrous and suspicious. This addition was Wilder’s idea because, as he told the director, “From that time on, no one will know if I’m lying or telling the truth.” From that moment on, every eye roll or smirk he offers can seem playful or devious, or both. In other words, perfectly fitting for a secretive chocolate factory king with a questionable agenda.

Still, there is something missing from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory that made the book sing. Dahl was “infuriated” by the plot changes, which included Charlie and Grandpa Joe stealing Wonka’s fizzy lifting drinks, and thought the musical numbers were “saccharine, sappy, and sentimental.” Moreover, he didn’t think enough emphasis was put on Charlie since it’s his story more than Wonka’s. He often expressed desire for another adaptation. While he passed away in 1991, it would take 14 years for someone else to pick up the mantle.

What Tim Burton’s Adaptation Does Better (and Also Worse)

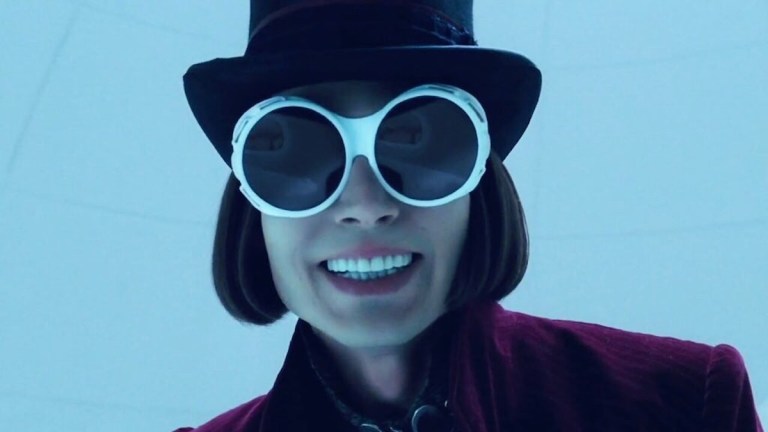

The news that Tim Burton would be adapting Roald Dahl seemed like the most perfect match of creator and material. Burton’s Gothic styling and penchant for tales of quirky outsiders pushing against staid traditionalism was already heavily influenced by Dahl, and he seemed to have the perfect understanding of what made the author’s books so special. 2005’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was highly budgeted ($150 million), had an Oscar-nominated star in the role of Wonka (Johnny Depp), and the approval of Dahl’s widow, Felicity, who declared the film’s team to be “absolutely unbeatable.” It seemed to pay off, as the movie remains the highest-grossing film adaptation based on a Roald Dahl novel, with $475 million to its name. Indeed, in many ways, it nails the source material.

Burton’s version more fully adheres to the book’s plot, particularly in how all the children get their just desserts. He brings back the squirrel scene from the novel where the spoiled Verruca Salt is deemed a bad nut and tossed into the trash by the trained rodents, and it ends up being one of the film’s highlights. His version Charlie, played by future Good Doctor Freddie Highmore, is the shy optimist of the novel who treasures his family even as they struggle with cartoonish levels of poverty. Burton also retains the original Oompa Loompa songs from the book and lets his regular composer Danny Elfman off the leash to compose numbers that include homages to hair metal and the Beatles.

It was a surprise to literally nobody that Burton’s adaptation is stunning to look at. The factory is equal parts sumptuous (that chocolate river!) and sinister, making it look like part of Gotham City from the earliest Batman films. The cartoonish quality of Quentin Blake’s illustrations, which are as beloved by readers as Dahl’s words, are evoked in the larger-than-life production work and deliberately grotesque character design. Every kid seems to have the sickly pallor of a haunted Victorian doll, making the unreal nature of their fates seem all the stranger. The world outside the factory is just as strange, pitched somewhere between The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and a Lisa Frank trapper keeper. To be immersed in Burton’s world is to be thoroughly in Dahl’s scope.

But where Burton stumbles is with Wonka himself. Depp’s performance was often compared to Michael Jackson, seen more as off-putting and actively malicious than subtly suspicious like Wilder’s. While this Wonka gets some good jokes, he is far less appealing to watch, and you do wonder why none of the kids and their parents run away within five seconds of meeting him. This is especially bothersome because Wonka gets the biggest character arc of the film, with Burton adding a sad childhood backstory involving an angry dentist father (played by the always-welcome Christopher Lee). Burton has often been dinged for daddy issues in his films, but it’s never felt more evident or forced as it does here.

Yet in terms of sheer aesthetic delight, Burton can’t help but come out on top. The benefits of a bigger budget are on display in his film, and he had the canvas to explore the endless imagination of Dahl. While both he and Burton told stories rooted in realism, they flourished in tales of the unreal, places where aspects are familiar but inflated to grotesque new heights. How can you not feel engulfed by this version of our world where everyone is strange and repulsive and totally obsessed with chocolate? The style is big but the emotions are grounded; we’ve all wanted more, and sometimes getting it is a curse. What could be more appropriately Dahl-esque than that?

Why No Roald Dahl Adaptation Fully Embodies His Work

Dahl adaptations struggle with his tone. There is a malicious quality to the best Dahl books, whether it’s Wonka’s moral ambiguity as he watches children be tortured or the gruesome mouse transformations in The Witches. The entire plot of George’s Marvelous Medicine hinges on the physical agony of an old woman. Few are safe in his worlds, but especially adults, who are typically shown as negligent narcissists who either don’t know their kids’ pain or don’t care. The weakest adaptations tone this down, such as Robert Zemeckis’ remake of The Witches, a stark contrast to the undiluted nightmare fuel of Nicolas Roeg’s version (and even Roeg watered down the novel’s extremely bleak “happy” ending, which made Dahl furious and threaten to badmouth the film publicly to tank its release.)

At its heart, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a deeply moralistic tale wherein a lot of kids suffer for the crimes of adults. If you’re too fat, too rude, or too obnoxious, you’re going to face the consequences of that, dictated by a shady business owner with indentured servants from Africa. It’s a bleak story and obviously a deeply problematic one, but also there’s a reason kids have latched onto it for so long. If the world is a cruel place then at least Roald Dahl doesn’t sugarcoat that, although he offers some delicious instances of revenge for those who deserve it. Frankly, that’s a lot for a filmmaker to take on, even without a studio executive breathing down their neck and worrying about the MPAA’s rating decision.

What this also means is that neither adaptation of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory can quite bring itself to peek over the edge into Dahl’s sly darkness, let alone dive headfirst into the river and revel in it. The 1971 version has a Wonka with a more believably sinister agenda, but the grotesqueries of the novel feel more aesthetically embodied via Burton’s lens. Charlie is a better character in the first film but more thematically consistent in the second, and he’s still not really the focus of either story as Dahl desired. Both movies are the Wonka Show, for better or worse.

They both falter in near-identical ways when it comes to both the Oompa Loompas and Augustus Gloop. The former are so staggeringly racist in Burton’s film that you’re stunned the studio kept it in the final product, and both films treat Gloop as a monster to be obliterated because he’s overweight. Burton in particular shoots him gorging on chocolate (in a chocolate factory!) as though he’s a monster in The Evil Dead.

In November 2021, Netflix bought the rights to Dahl’s back-catalog and announced plans to make several adaptations of his work, including the musical version of Matilda and Wes Anderson’s recent take on several shorts including The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar.

Their schedule also includes an “animated series event” based on both Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and the novel’s sequel Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator. We certainly still have room to make the truly perfect Chocolate Factory adaptation, but at least the two versions we currently have offer a mish-mash of ideas and joy that excite audiences to this day.